Modeling pragmatic inference

Day 2: Enriching the literal interpretations

Application 1: Scalar implicature

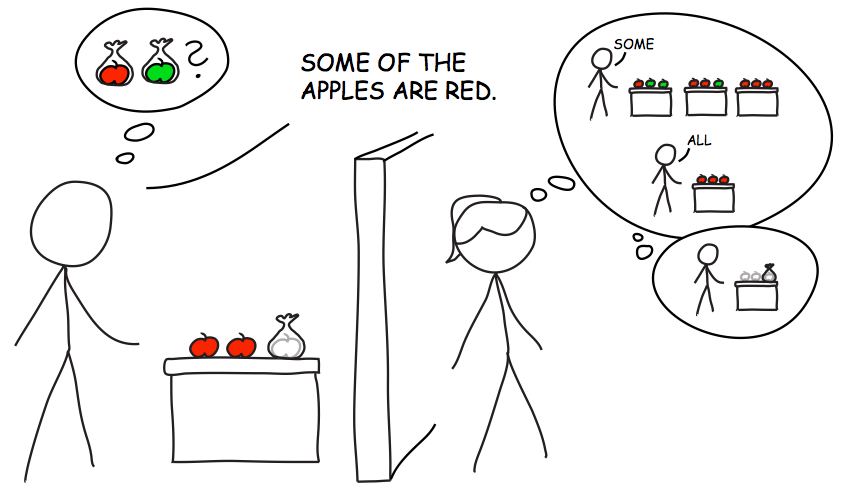

Scalar implicature stands as the poster child of pragmatic inference. Utterances are strengthened—via implicature—from a relatively weak literal interpretation to a pragmatic interpretation that goes beyond the literal semantics: “Some of the apples are red,” an utterance compatible with all of the apples being red, gets strengthed to “Some but not all of the apples are red.” The mechanisms underlying this process have been discussed at length. reft:goodmanstuhlmuller2013 apply an RSA treatment to the phenomenon and formally articulate the model by which scalar implicatures get calculated.

Assume a world with three apples; zero, one, two, or three of those apples may be red:

// possible states of the world

var statePrior = function() {

return uniformDraw([0, 1, 2, 3])

};

statePrior() // sample a state

Next, assume that speakers may describe the current state of the world in one of three ways:

// possible utterances

var utterancePrior = function() {

return uniformDraw(['all', 'some', 'none']);

};

// meaning funtion to interpret the utterances

var literalMeanings = {

all: function(state) { return state === 3; },

some: function(state) { return state > 0; },

none: function(state) { return state === 0; }

};

var utt = utterancePrior(); // sample an utterance

var meaning = literalMeanings[utt]; // get its meaning

[utt, meaning(3)] // apply meaning to state = 3

With this knowledge about the communcation scenario—crucially, the availability of the “all” alternative utterance—a pragmatic listener is able to infer from the “some” utterance that the “all” utterance describes an unlikely state. In other words, the pragmatic listener strengthens “some” via scalar implicature.

Technical note: Below, cache is used to save the results of the various Bayesian inferences being performed. This is used for computational efficiency when dealing with nested inferences.

// Here is the code from the basic scalar implicature model

// possible states of the world

var statePrior = function() {

return uniformDraw([0, 1, 2, 3])

};

// possible utterances

var utterancePrior = function() {

return uniformDraw(['all', 'some', 'none']);

};

// meaning funtion to interpret the utterances

var literalMeanings = {

all: function(state) { return state === 3; },

some: function(state) { return state > 0; },

none: function(state) { return state === 0; }

};

// literal listener

var literalListener = cache(function(utt) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var state = statePrior()

var meaning = literalMeanings[utt]

condition(meaning(state))

return state

})

});

// set speaker optimality

var alpha = 1

// pragmatic speaker

var speaker = cache(function(state) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var utt = utterancePrior()

factor(alpha * literalListener(utt).score(state))

return utt

})

});

// pragmatic listener

var pragmaticListener = cache(function(utt) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var state = statePrior()

observe(speaker(state),utt)

return state

})

});

print("pragmatic listener's interpretation of 'some':")

viz.auto(pragmaticListener('some'));

Exercises:

- Explore what happens if you make the speaker less optimal.

- Add a new utterance.

- Check what would happen if ‘some’ literally meant some-but-not-all.

- Change the relative probabilities of the various states.

Application 2: Scalar implication and speaker knowledge

Capturing scalar implicature within the RSA framework might not induce waves of excitement. However, by implementing implicature-calculation within a formal model of communication, we can also capture its interactions with other pragmatic factors. Goodman and Stuhlmüller (2013) explored what happens when the speaker only has partial knowledge about the state of the world (Fig. 1). Below, we explore this model, taking into account the listener’s knowledge about the speaker’s epistemic state: whether or not the speaker has full or partial knowledge about the state of the world.

In the extended Scalar Implicature model, the pragmatic listener infers the true state of the world not only on the basis of the observed utterance, but also the speaker’s espistemic access .

// pragmatic listener

var pragmaticListener = cache(function(access,utt) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var state = statePrior()

observe(speaker(access,state),utt)

return numTrue(state)

})

});

We have to enrich the speaker model: first the speaker makes an observation of the true state with access . On the basis of the observation and access, the speaker infers the true state.

///fold:

// tally up the state

var numTrue = function(state) {

var fun = function(x) {

x ? 1 : 0

}

return sum(map(fun,state))

}

///

// red apple base rate

var baserate = 0.8

// state builder

var statePrior = function() {

var s1 = flip(baserate)

var s2 = flip(baserate)

var s3 = flip(baserate)

return [s1,s2,s3]

}

// speaker belief function

var belief = function(actualState, access) {

var fun = function(access,state) {

return access ? state : uniformDraw(statePrior())

}

return map2(fun, access, actualState);

}

print("1000 runs of the speaker's belief function:")

viz.auto(repeat(1000,function() {

numTrue(belief([true,true,true],[true,true,false]))

}))

Exercise: See what happens when you change the red apple base rate.

The speaker then chooses an utterance to communicate the true state that likely generated the observation that the speaker made with access .

// pragmatic speaker

var speaker = cache(function(access,state) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var utterance = utterancePrior()

var beliefState = belief(state,access)

factor(alpha * literalListener(utterance).score(beliefState))

return utterance

})

});

The speaker’s utility function remains unchanged, such that utterances are chosen to minimize cost and maximize informativity.

The intuition (which Goodman and Stuhlmüller validate experimentally) is that in cases where the speaker has partial knowledge access (say, she knows about only two out of three relevant apples), the listener will be less likely to calculate the implicature (because he knows that the speaker doesn’t have the evidence to back up the strengthened meaning).

///fold:

// tally up the state

var numTrue = function(state) {

var fun = function(x) {

x ? 1 : 0

}

return sum(map(fun,state))

}

///

// Here is the code from the Goodman and Stuhlmüller speaker-access SI model

// red apple base rate

var baserate = 0.8

// state prior

var statePrior = function() {

var s1 = flip(baserate)

var s2 = flip(baserate)

var s3 = flip(baserate)

return [s1,s2,s3]

}

// speaker belief function

var belief = function(actualState, access) {

var fun = function(access,state) {

return access ? state : uniformDraw(statePrior())

}

return map2(fun, access, actualState);

}

// utterance prior

var utterancePrior = function() {

uniformDraw(['all','some','none'])

}

// meaning funtion to interpret utterances

var literalMeanings = {

all: function(state) { return all(function(s){s}, state); },

some: function(state) { return any(function(s){s}, state); },

none: function(state) { return all(function(s){s==false}, state); }

};

// literal listener

var literalListener = cache(function(utt) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var state = statePrior()

var meaning = literalMeanings[utt]

condition(meaning(state))

return state

})

});

// set speaker optimality

var alpha = 1

// pragmatic speaker

var speaker = cache(function(access,state) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var utt = utterancePrior()

var beliefState = belief(state,access)

factor(alpha * literalListener(utt).score(beliefState))

return utt

})

});

// pragmatic listener

var pragmaticListener = cache(function(access,utt) {

return Infer({method:"enumerate"},

function(){

var state = statePrior()

observe(speaker(access,state),utt)

return numTrue(state)

})

});

print("pragmatic listener for a full-access speaker:")

viz.auto(pragmaticListener([true,true,true],'some'))

print("pragmatic listener for a partial-access speaker:")

viz.auto(pragmaticListener([true,true,false],'some'))

Exercise:

- Check the predictions for the other possible knowledge states.

- Compare the full-access predictions with the predictions from the simpler scalar implicature model above. Why are the predictions of the two models different? How can you get the model predictions to converge?

We have seen how the RSA framework can implement the mechanism whereby utterance interpretations are strengthened. Through an interaction between what was said, what could have been said, and what all of those things literally mean, the model delivers scalar implicature. And by taking into account awareness of the speaker’s knowledge, the model successfully blocks implicatures in those cases where listeners are unlikely to access them.

The models we have so far considered strengthen the litereal interpretations of our utterances: from “blue” to “blue circle” and from “some” to “some-but-not-all.” Next, we consider what happens when we use utterances that are literally false. As we’ll see, the strategy of strengthening interpretations by narrowing the set of worlds that our utterances describe will no longer serve to capture our meanings.

Application 3: Hyperbole and the Question Under Discussion

If you hear that someone waited “a million years” for a table at a popular restaurant or paid “a thousand dollars” for a coffee at a hipster hangout, you are unlikely to conclude that the improbable literal meanings are true. Instead, you conclude that the diner waited a long time, or paid an exorbitant amount of money, and that she is frustrated with the experience. Whereas blue circles are compatible with the literal meaning of “blue,” five-dollar coffees are not compatible with the literal meaning of “a thousand dollars.” How, then, do we arrive at sensible interpretations when our words are literally false?

reft:kaoetal2014 propose that we model hyperbole understanding as pragmatic inference. Crucially, they propose that we recognize uncertainty about communicative goals: what Question Under Discussion (QUD) a speaker is likely addressing with their utterance. To capture cases of hyperbole, Kao et al. observe that speakers are likely communicating—at least in part—about their attitude toward a state of the world (i.e., the valence of their affect). QUDs are modeled as summaries of the full world states, which take into account both state and valence (a binary positive/negative variable) information:

///fold:

// Round x to nearest multiple of b (used for approximate interpretation):

var approx = function(x,b) {

return b * Math.round(x / b)

};

///

var qudFns = {

state : function(state, valence) {return {state: state} },

valence : function(state, valence) {return {valence: valence} },

stateValence : function(state, valence) {return {state: state, valence: valence} },

approxState : function(state, valence) {return {state: approx(state, 10) } },

};

print("QUD values for state (i.e., price)=51, valence (i.e., is annoyed?) = true")

print("valence QUD")

var fun = qudFns["valence"]

print(fun(51, true))

print("state QUD")

var fun = qudFns["state"]

print(fun(51, true))

print("stateValence QUD")

var fun = qudFns["stateValence"]

print(fun(51, true))

print("approxState QUD")

var fun = qudFns["approxState"]

print(fun(51, true))

The literal listener infers the answer to the QUD, assuming that the utterance he hears is true of the state. In the full version, Kao et al. model liteners’ reactions to statements about the price of electric kettles. They empirically estimate the prior knowledge people carry about kettle prices, as well as the probility of getting upset (i.e., experiencing a negatively-valenced affect) in response to a given price.

///fold:

// Round x to nearest multiple of b (used for approximate interpretation):

var approx = function(x,b) {

return b * Math.round(x / b)

};

///

// Define list of kettle prices under consideration (possible price states)

var states = [50, 51, 500, 501, 1000, 1001, 5000, 5001, 10000, 10001];

// Prior probability of kettle prices (taken from human experiments)

var statePrior = function() {

return categorical([0.4205, 0.3865, 0.0533, 0.0538, 0.0223, 0.0211, 0.0112, 0.0111, 0.0083, 0.0120],

states)

};

// Probability that given a price state, the speaker thinks it's too

// expensive (taken from human experiments)

var valencePrior = function(state) {

var probs = {

50 : 0.3173,

51 : 0.3173,

500 : 0.7920,

501 : 0.7920,

1000 : 0.8933,

1001 : 0.8933,

5000 : 0.9524,

5001 : 0.9524,

10000 : 0.9864,

10001 : 0.9864

}

var tf = flip(probs[state]);

return tf

};

var qudFns = {

state : function(state, valence) {return {state: state} },

valence : function(state, valence) {return {valence: valence} },

stateValence : function(state, valence) {return {state: state, valence: valence} },

approxState : function(state, valence) {return {state: approx(state, 10) } },

};

// Literal interpretation "meaning" function;

// checks if uttered number reflects price state

var meaning = function(utterance, state) {

return utterance == state;

};

var literalListener = cache(function(utterance, qud) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var state = statePrior() // uncertainty about the state

var valence = valencePrior(state) // uncertainty about the valence

var qudFn = qudFns[qud]

condition(meaning(utterance,state))

return qudFn(state,valence)

})

});

Exercises:

- Suppose the literal listener hears the kettle costs

10000dollars with the"stateValence"QUD. What does it infer?- Test out other QUDs. What aspects of interpretation does the literal listener capture? What aspects does it not capture?

- Create a new QUD function and try it out with “the kettle costs

10000dollars”.

This enriched literal listener does a joint inference about the state and the valence but assumes a particular QUD by which to interpret the utterance. Similarly, the speaker chooses an utterance to convey a particular value of the QUD to the literal listener:

var speaker = cache(function(qValue, qud) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var utterance = utterancePrior()

factor(alpha * literalListener(utterance,qud).score(qValue))

return utterance

})

});

To model hyperbole, Kao et al. posited that the pragmatic listener actually has uncertainty about what the QUD is, and jointly infers the world state (and speaker valence) and the intended QUD from the utterance he receives. That is, the pragmatic listener simulates how the speaker would behave with various QUDs.

var pragmaticListener = cache(function(utterance) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var state = statePrior()

var valence = valencePrior(state)

var qud = qudPrior()

var qudFn = qudFns[qud]

var qValue = qudFn(state, valence)

observe(speaker(qValue, qud),utterance)

return {state : state, valence : valence}

})

});

Here is the full model:

///fold:

// Round x to nearest multiple of b (used for approximate interpretation):

var approx = function(x,b) {

return b * Math.round(x / b)

};

///

// Here is the code from the Kao et al. hyperbole model

// Define list of kettle prices under consideration (possible price states)

var states = [50, 51, 500, 501, 1000, 1001, 5000, 5001, 10000, 10001];

// Prior probability of kettle prices (taken from human experiments)

var statePrior = function() {

return categorical([0.4205, 0.3865, 0.0533, 0.0538, 0.0223, 0.0211, 0.0112, 0.0111, 0.0083, 0.0120],

states)

};

// Probability that given a price state, the speaker thinks it's too

// expensive (taken from human experiments)

var valencePrior = function(state) {

var probs = {

50 : 0.3173,

51 : 0.3173,

500 : 0.7920,

501 : 0.7920,

1000 : 0.8933,

1001 : 0.8933,

5000 : 0.9524,

5001 : 0.9524,

10000 : 0.9864,

10001 : 0.9864

}

var tf = flip(probs[state]);

return tf

};

// Prior over QUDs

var qudPrior = function() {

return categorical([0.17, 0.32, 0.17, 0.17, 0.17],

["state", "valence", "stateValence", "approxState", "approxStateValence"])

};

var qudFns = {

state : function(state, valence) {return {state: state} },

valence : function(state, valence) {return {valence: valence} },

stateValence : function(state, valence) {return {state: state, valence: valence} },

approxState : function(state, valence) {return {state: approx(state, 10) } },

approxStateValence: function(state, valence) {return {state: approx(state, 10), valence: valence } }

};

// Define list of possible utterances (same as price states)

var utterances = states;

// Precise numbers are costlier

var utterancePrior = function() {

categorical([0.18, 0.1, 0.18, 0.1, 0.18, 0.1, 0.18, 0.1, 0.18, 0.1],

utterances)

};

// Literal interpretation "meaning" function; checks if uttered number

// reflects price state

var meaning = function(utterance, state) {

return utterance == state;

};

// Literal listener, infers the qud value assuming the utterance is

// true of the state

var literalListener = cache(function(utterance, qud) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var state = statePrior()

var valence = valencePrior(state)

var qudFn = qudFns[qud]

condition(meaning(utterance,state))

return qudFn(state,valence)

})

});

// set speaker optimality

var alpha = 1

// Speaker, chooses an utterance to convey a particular value of the qud

var speaker = cache(function(qValue, qud) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var utterance = utterancePrior()

factor(alpha*literalListener(utterance,qud).score(qValue))

return utterance

})

});

// Pragmatic listener, jointly infers the price state, speaker valence, and QUD

var pragmaticListener = cache(function(utterance) {

return Infer({method : "enumerate"},

function() {

var state = statePrior()

var valence = valencePrior(state)

var qud = qudPrior()

var qudFn = qudFns[qud]

var qValue = qudFn(state, valence)

observe(speaker(qValue, qud), utterance)

return {state : state, valence : valence}

})

});

var listenerPosterior = pragmaticListener(10000);

print("marginal distributions:")

viz.marginals(listenerPosterior)

print("pragmatic listener's joint interpretation of 'The kettle cost $10,000':")

viz.auto(listenerPosterior)

Exercises:

- Try the

pragmaticListenerwith the other possible utterances.- Check the predictions of the

speakerfor theapproxStateValenceQUD.

By capturing the extreme (im)probability of kettle prices, together with the flexibility introduced by shifting communicative goals, the model is able to derive the inference that a speaker who comments on a “$10,000 kettle” likely intends to communicate that the kettle price was upsetting. The model thus captures some of the most flexible uses of language: what we mean when our utteranes are literally false.

Both the Scalar Implicature and Hyperbole models operate at the level of full utterances, with conversational participants reasoning about propositions. In the next chapter, we begin to look at what it would take to model reasoning about sub-propositional meaning-bearing elements within the RSA framework.

Table of Contents